Musings on the Re-Emergence High Frequency SBD Training

- Taylor Shadgett

- Mar 6

- 13 min read

I am going to bring you back to the bronze age of raw powerlifting, let’s say 2014-2016. CrossFit has changed the strength and conditioning game by popularizing the barbell. Lifting heavy circles was becoming more common, more popular, and more accessible. Raw powerlifting is growing since the IPF created a classic division in 2012, answering the requests of the lifters, as high level IPF lifters were competing at the Raw Unity Meets. I think YouTube and Instagram played a big part in making powerlifting more popular, as most of the media surrounding resistance training at the time was still mostly related to bodybuilding and physique sport. Mysterious Sheiko programs were showing up on the internet, crushing the will of the most enthusiastic of people thinking they had finally had access to the soviet secrets. My favourite exercise translation was “A Press Laying.” Along comes Dr. Mike Zourdos doing experiments with DUP models, immediately motivating people to change their programs because he unlocked the newest secret to maximal strength and hypertrophy gainz.

This period was characterized by a lot of high frequency, high volume, submaximal training in raw powerlifting. Real ones will remember the sub6gang. More and more of the research was pointing to the idea that training volume drives both strength and hypertrophy adaptations best, while increased frequencies were also being experimented with as lifters became more in tune with the idea of wanting to practice the lifts as often as possible. The idea that you can probably handle more work, and make better gainz, if you separate it over the week. On top of that, overreaching was far more common and more popular. The idea that we could insert overreaching weeks, even blocks, where the training dosage was purposely above our Maximal Recoverable Volume, following it up with tapers or deloads could illicit greater levels of supercompensation and greater peaks.

I drank the Kool-Aid. I had been successful enough in my first few meets but had not really made tons of progress in my first couple years of powerlifting. When I witnessed a fellow Coach, co-worker, training partner, and now long-time friend, squatting, benching, and deadlifting 3-4 times per week, with great technique, never to failure, subsequently performing very well at the first meet I handled him at, I was immediately intrigued. At the time I was training with a pretty basic split. Essentially a 4x Upper/Lower split, with squat, bench, and deadlift each having their day of priority. I was always so sore from deadlifting, and Nikk would say things like “I bet if you just deadlifted more often you would be less sore.” I bet you would be better at benchpress if you just practiced more often.”

I took my training plan, spread the work out over more days of training, focused on practicing the lifts at submaximal volumes, improving technique and bar speeds and ultimately leading to the training plan that built my first 300kgs squat. Wanting more, believing I could do more, needing to handle more, I increased my frequency of each lift to 4x per week, and added more work. Funny, because one of the things I am very hesitant to do as a coach is add work when a program is working.

Our culture is very “what can I add to this system to improve output?” verses “What can I remove from this system to improve output?” I can curb the appetites of clients but have never been able to curb those appetites in myself. I even made this mistake more recently when training was feeling very good, I was healthy, and I thought I might be able to drive workloads up in an attempt to compete with my former self. Silly Taylor, always wanting to do more.

If you want to the good at a sport, you should practice that sport every day. Anyone who has competed in a sport other than powerlifting knows that you must practice all the time if you want to be great. Even sports with very high contact forces like football and hockey still find ways to practice almost every day. This has always been one of my main arguments for attempting to increase frequency for new clients. More practice means more skill, more skill means greater loads on the bar. Now, the argument against practicing powerlifting every day is that either the training would wear people out, or that some of the training would have to be so light that it did not actually stimulate any adaptations or technique development, and that you would probably just be better off resting. Pawel has been challenging that idea lately, his shining star Agata Sitko being the catalyst for this change.

Does training need to be stimulative every day? Does it need to be heavy enough that it stresses our nervous system to illicit strength adaptations? Does it need to be proximal enough to failure that it creates enough peripheral stress to stimulate hypertrophy? Even when I trained with a 4x SBD frequency I still wanted all the sessions to be hard or to have a movement or variation that was prioritized and trained hard. Does your second squat and deadlift even need to be that hard? Or do you just want it to be hard, even want to need it to be hard? I battle this question more and more lately. It is a combination of my understanding of what we think drives strength and hypertrophy development, my desire to work hard, and my expectations that others do the same. Light training is boring, easy training is boring, and then there is the bias I have developed that super light technique training will not transfer to 1RM development. What evidence do I even have of this?

My Youngblood iterations of high frequency SBD training had no load management tools, no autoregulation, always anchored on doing more work, increasing volumes or intensities every session of every week, and quite frankly used inappropriate workloads for most people, including myself. They also lacked specificity in their own way. I was chatting about these programs with Mr. Krabshark recently, admitting that my capacity to do work in the 70%-80% range far exceeded the amount of training transfer I got from these prescriptions. I can remember the 6x4 at 240kgs squat session. Culminating with a 302.5kgs squat in competition. 8 years of coaching and training later, I am not sure those numbers compute.

So, if I wanted to apply this style of training again, what would I change? To start, I would really lean into the idea that all your training does not need to be so stressful to our neuromuscular system to be productive. I have even been trying to lean into this idea more and more with my current training system. My bias is that training must stress our nervous system aka it must be heavy enough that it is stressful enough that it drives strength adaptations. My next bias is that if it is not doing that, it must be proximal enough to failure that it is going to stimulate hypertrophy in the muscles being worked. Stealing from a metaphor Jason Tremblay, if you create more little workers in your body, those workers should be able to move more weights. At the end of the day, contraction of muscle tissue moves the weight. Even with tempo training or long pause training I am usually trying to do one of these two things. Within my current system, do priority 2 squat, bench, and deadlift variations need to be as intense as I am prescribing? Note, high level training outcomes still require high levels of intention. When I am questioning whether certain parts of training need to be that hard, I still expect the need for that training to be full of intention, maybe more than usually since the main goal is perfect practice. Being overly intentional with your technique on a day dedicated to practicing your technique should make things more automatic on the heavy day so that you don’t think, you just focus on standing up.

Training obviously needs to be sufficiently hard some of the time, I have made that argument here, but maybe not all the time? I don’t know that I have any anecdotal evidence that if I prescribed easier, sub 6 RPE, practice-based priority 2 training that people would get worse results. One the other hand I don’t know that my currents methods of prescribing strength or hypertrophy-based priority 2 sessions gets people better results either. For all I know I am creating stress and disruption that is bleeding back into priority 1 sessions at different points in the microcycle. As much as I know that hard training drives adaptation, I also know that peaks in intensity are the thing that really drive strength adaptation. I need to work to fine tune so that I create more peaks in intensity. If making priority-2 squat strength or hypertrophy based makes it so that I end up lifting lower weights on the priority-1 session, then over the long term I may be handicapping progress. This is a difficult dichotomy for any strength coach, because at the same time what you prescribe in the rest of the microcycle may be the thing really driving performance in the priority performance indicator. Some people squat better when they do pause squats on another day. Other people bench well when they press against bands or with a slingshot in their training. Agata’s coach Pawel says her deadlift does not perform well unless they are doing pause deadlifts in the microcycle. Trying to find the goldilocks zone of training dose for priority-2 variations is challenging and ever changing.

I have stayed in contact with one of my former clients who is also a coach, he and I have been chatting about the high frequency training idea being re-popularized by Agata’s success. When we worked together his training was already characterized by multiple SBD days. Our last training plan had 3 SBD days with another training session dedicated to bench and upper body accessories. While his training was productive and successful, looking back at our results over time, and how the training transferred to the platform leaves me wanting. If I look at his training from our lead up to USAPL Raw Nationals in 2024 I see myself potentially committing the same errors I have been talking about, all his training attempts to be stimulative in some way. Multiple sets per day above RPE 6 or 7, and all accessory work all trained proximal to failure. Would we have had more success with work that was easier or less proximal to failure? Was I trying too hard to make every session a priority? Who knows, there is never any way of truly knowing answers to questions like this. I am just working to challenge my own thoughts and beliefs about programming, in hopes of unlocking more secrets for more gainz and developing better systems of strength development.

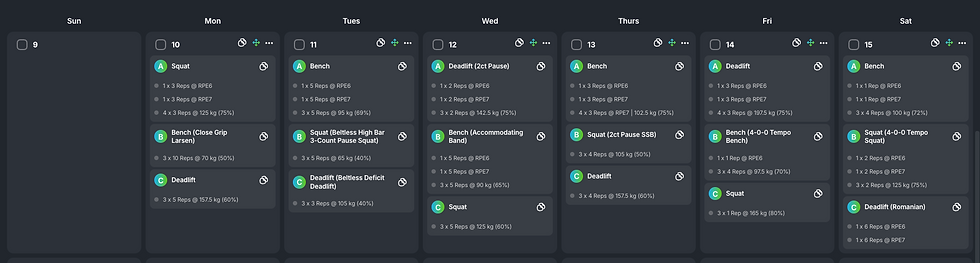

While I would probably still squat first in every session, I wrote the plan with the priority lift at the top to keep myself organized. One major difference I would note is that as far as I have seen from Pawel’s programming strategies, he plans one main priority 1 SBD Day, while I have spread the priority-1 lifts across the week.

Another note is that I would prescribe all the exercises from Priority 4 and below using percentages. The goal being to control the loading on the lower priority days, while still allowing the athlete to practice. If I was to run this as an experiment, I would probably hold the lower priority workloads constant, at least for the first block or 2, to reduce noise in the system while also controlling the load that the athlete puts on the bar. Those lower priority movements really need to be low volume, low RPE, skill development and motor patterning. As far as my understanding goes this is how Pawel transitioned Agata’s frequency up. He had data on how 3-4x SBD training frequency, so he added in multiple days of light SBD training and paid attention to see if there was any interference.

It was an interesting exercise for both of us as he then shared back the training that he had been doing himself, and while he was not training 6 days per week, it was cool to compare how we would begin to attempt to plan something like this.

If I was to try to start someone with higher frequency SBD training I would probably start with just 3 days per week. I would have a conversation with the athlete to figure out whether they wanted a main SBD priority 1 session, or to spread their priority lifts across the week. My personal bias would lean towards spreading the priority 1 movements across the week, although I have programmed priority 1 comp SBD session in the past for myself and for others. I would argue that the first option would yield greater specificity, it runs the risk of being a very long session, and the potential for lower performance in the priority 1 deadlift by the time you got there. At the same time, it would prepare an athlete to be in shape for a competition. Splitting the main lifts across the week should allow for greater performance in training, while making it easier to keep session times consistent. It also gives the athlete the goal of focusing on one main lift per training session. I would probably initiate this experiment by keeping the training very vanilla on paper, with very minimal workloads, and let the training run it’s course week after week and just observe what happens. One strategy I like is to make lower priority lifts percentage-based work that should be more than manageable, facilitating good practice during those sessions, allowing the lifter to go in and execute without worrying about load selection, also letting the RPE based priority-1 lift take the reins of the program.

As usual, one of the problems with strategies like this is that they can be boring. Knowing that you are going in to lift the same weights as last week can be unexciting, and training well shy of failure and/or capacity doesn’t scratch my itch either, even if there is another lift in the session that is the main priority. I don’t know that I would call it long term gratification but even controlling emotions and outputs for lower priority training sessions can be difficult for some people. Maybe this is just my bias, “what is the point of doing 4 sets of 3 when I can do 1 set of 12 with this weight?”

A non-traditional DUP model is an easy enough place to start. For those of you that are unfamiliar with DUP, Daily Undulating Periodization is just a fancy way or saying we are using different volumes and intensities on different days of training to illicit a different response and keep training novel. A non-traditional DUP model has one day of training dedicated to hypertrophy, then one for power, then one for strength. For simplicity, Let’s say that strength work is in the 1-5 rep range, 75% and above, moderate set counts, RPE 6+. Power work is also in the same 1-5 rep range, usually 1-3, but much less intensity, anywhere from 30%-60%, low total volumes very low RPE. Hypertrophy work is anywhere 6 reps and above, with our best bang for our buck occurring from 6-12

reps, generally 60%-75% high volume, higher RPE. Without getting too into the

weeds, note that this is just a good starting point. You do not have to do DUP exactly this way. DUP could be 3 strength days, 3 Hypertrophy days if you are a bodybuilder or in offseason, 2 strength days and a power day, etc. etc., there are many different combinations. For our purposes we will make the strength day the first session, as our main priority is strength.

My bias is to put the most time between the session with the highest volume, and the session that is the priority. The lower volume “power” day may also prime the athlete for the heaviest session. If you prefer to use the second option, I will make the two days of complete rest come before the priority 1 session. Now, some of these training sessions look like they

could be gruelling, and for some people it may be better to move priorities around.

Balancing priorities gets a little tougher here, as you want to try to not let Squat and DL training interfere with each other from session to session, and within a session, an example being if you put high volume squat-2 on Friday, it is plausible that it will negatively impact deadlift-1. The way I have things set up, soreness from squat 2 may impact that training day anyway, but I was trying to put the most complete rest between deadlift-1 and squat-1.

Our next tool in the toolbox is to use different SBD variations to make the training even more novel, self-limit certain training days, and work on weak points.

One tool I have not even mentioned is RPE. RPE opens another box of increased novelty, individuality, specificity, and variation, on top of the major benefit of autoregulating training load. I would probably keep the “power” days % based as those weights will be too light to accurately gauge RPE.

Whether you use this setup, these variations, prescriptions, or even these days of training is obviously up to you. I am just trying to illustrate some concepts. Assuming you found a training dose that you were recovering from, adapting too, and successful with, if you still really wanted to drive your SBD up for practice purposes, I would probably think about adding training sessions like our “power” prescriptions. From there observing whether the lighter sessions are creating interference with progress in the priority sessions. You could even use your original framework but then drop 20-30% from each training day while using the same variations, sets, and reps.

Now, one note I would make about this setup is that some of the sessions would be much longer than others, which has positives and negatives, but if you

wanted to balance that out, and provide one or two main lifts to focus on in each of your 6 sessions I would just take the current setup and move things around so that you always have an exciting lift to look forward to in each session.

I made this note earlier, but one thing I have been able to observe is that Pawel has his athlete’s complete priority-1 SBD all on the same day, and he even lines this session up with the day the athlete will be competing. While this will make for one particularly long session, it creates a high specificity stimulus and increases the chances of repeatability and a better indication of what to expect on game day. I have dubbed this the Final Boss.

Frankly, I have no idea how this program would go. I have just been trying to work my brain around how I might begin to program 6 SBD sessions in a week. The amount of practice would be highly beneficial for a lot of people if workload was managed appropriately. I am fascinated by the coaches pushing the envelope and finding better systems of development, creating more with more, or less if you think about the fact that they are clearly getting a lot of training transfer out of a lot of what might look like some very light training on paper. If someone wants to run this program and let me know how it goes that would be great.

Until next time, Send It and Bend It.

Comments